Teaching The Stamp Act Protests in the Context of Current Events

The Stamp Act Protests

The "Respectable Populace" Control the Streets

by Jeff Schneider

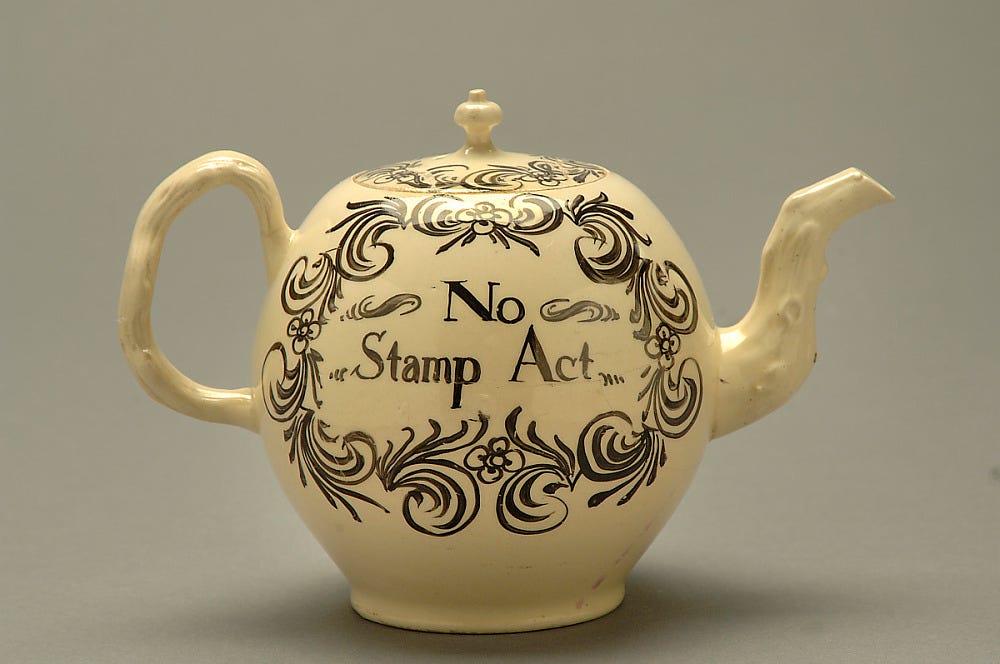

Teapot made in Great Britain for Sale in American Colonies 1766 - 1770

In the wake of the Black Action Movement protests against the police killing of George Floyd last year there were a number of articles in newspapers attempting to place the demonstrations in the context of American history. A journalist, Stacy Schiff, wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times on August 16, 2020 in which she characterized the Stamp Act protests, the Boston Massacre and the Tea Party as "good trouble" in John Lewis's phrase. However the center of her argument was that "we" mis-remember them as"tea parties" not how violent they actually were as though they had been conducted by well behaved adults not political actors creating violent trouble. Who is this "we?" Students in high school learn about the Stamp Act Riots. This is confused history. The tea party demonstrators destroyed 340 tea chests with axes and block and tackle heaving them overboard into Boston harbor costing more than 9,000 Lbs sterling. In order to use a block and tackle, you must be a skilled stevedore or warfinger, as they were called in the 18th century. Even elementary schoolers know they dressed up as Native Americans and broke the tea chests with tomahawks, but more importantly it leaves out the reason that they did it. If the tea had stayed on the ship in the harbor past 12 AM the colonists would have had to pay for the tea which they were refusing to buy, because it was subject to a tax passed by Parliament. Schiff complained that a group of boys were harassing the soldiers before the Boston Massacre in 1770 throwing stones in snow balls and shouting “Shoot! Shoot!” A week and a half before before an 11 year old boy named Christopher Seider had been killed by a shot gun during a demonstration against merchants who were breaking the boycott of British goods. There were serious tensions between the common soldiers and the townspeople because the soldiers were competing for jobs with the colonists. The aristocrats, who were the officers did not need the money, but the average soldier did. There were reasons for the demonstrations. They were not just making trouble.

Similarly, the Stamp Act protest was designed to prevent the enforcement of an illegal tax that the colonists opposed, because it was their right as Englishmen not to pay taxes not imposed by their own assemblies. These demonstrations were effective and organized to produce the results that the leaders of the colonies had wished. The people supported them. There were thousands of spectators silently watching the tea being dumped into the harbor and the Stamp Act would have affected everyone in the colonies because it taxed such common goods as playing cards, dice and government licenses for vendors, to leases and mortgages. She described how the protests in 1765 were minimized by Samuel Adams as the "frolic of a few boys to eat some cherries." Then she describes the demonstrators as gangs of teenagers not skilled men who could use block and tackle, pull down houses and take apart roofs.

The Loyal Nine or the Sons of Liberty, as they were later called, organized in every one of the thirteen colonies and recruited activists of mechanics (artisans) and laborers to produce acts of vandalism and intimidation of the officials appointed by the King's Minister George Grenville to prevent the Stamp Act from going into effect. These men were given their instructions by Paul Revere, Sam Adams and met with John Adams at times. Two Charleston fire companies were part of Sons of Liberty for example. They were not teenage boys, as claimed by Schiff. Most Americans do not know that no one in the colonies ever paid the Stamp Tax: only one of the appointed Distributors took the required oath, but as soon as he could, he left the stamped paper on a man of war and escaped "to parts unknown," according to the authors of the Stamp Act Crisis, Edmund and Helen Morgan. These protests were part of a European tradition of public theater protests, like charivari, which were conducted by the common people who had no other avenue to make their voices heard. Social historians call them crowds as the British experts on protests George Rude and Eric Hobsbawm have taught us.

The biggest riot during the anti-war movement was in 1968 when the police attacked the demonstration at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The famous chant, the "Whole World is Watching,"came from there. The other violence came from the police at the Columbia Strike and the National Guard at Kent State. It was only in Berkeley that there were regular fights between demonstrators and the police. All over the country SDS and the various committees to end the war marched peacefully until the Weathermen -- a very small splinter group of SDS called for terrorist attacks in the US. After they blew up the townhouse in Greenwich Village killing three of their own members and their terrorism began, it was confined to property not people. The rest of the New Left considered them a political disgrace to the movement.

The Civil Rights Movement was a non-violent series of organizations that led peaceful demonstrations that were attacked by police with dogs, firefighters, and racists at lunch counters, in buses during the freedom rides and on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Dr. King and the leaders of CORE and SNCC did not create violence and neither did Malcolm X when he was a Black Muslim or after he left: His most famous speech "The Ballot or the Bullet," was actually about voting rights despite the obvious threat in the title.

It is simply not true that the demonstrations of the 50s, 60s or the early 70s were sources of widespread violence. They accomplished enormous changes: Bringing down two presidents, ending the war in Vietnam, creating the women's movement, LGBTQ organizations, the American Indian Movement, and Hispanic and later Asian organizations. The culture of equality and diversity came from the movements of the 60s.

What scholars have found about the protests by Black Lives Matter in the summer of 2020 is that 93% of them were peaceful – in contradistinction to the Stamp Act protests. The remaining 7% included violence involving police which does not differentiate from those initiated by police and those initiated by the protesters.* That number of course, includes the cars driven by police into the protests in New York City and the car driven into the peaceful crowd that killed Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Virginia.

One

I taught the lesson on the Stamp Act soon after the Virginia Resolves, which you can see elsewhere on this site. The Stamp Act documents are striking because they describe the actions of the common people and show the violence that they perpetrated on the British authorities or those who had chosen to work for them to tax the colonists. These were white people protesting. It is a lesson for all of us, both because they are violent against the property of specific individuals, but they also did not injure anyone. They were organized by the future leaders of the Revolution. The chapter on the Stamp Act in the textbooks often describe these protests: These documents are the source. Students experience a new level of understanding of history in reading these. It is quite a surprise, actually.

Now let us turn to the lesson itself. I assigned two short documents to my gifted classes and Regents classes see #38 and # 39 in the PDF Letters on the Stamp Act Protests 8/1765** In addition my AP classes had to read a chapter from The Stamp Act Crisis called “Contagion.” *** All the students had to choose 5 sentences from the #38: one in the beginning, 3 in the middle and one at the end. Regardless they had to get to p.108. They also had to choose two sentences from the letter by Thomas Hutchinson. The AP classes chose 8 sentences from “Contagion” one from the beginning, one from the end and 6 spread out over the rest of the pages in between. Of course, they also had to comment on each sentence explaining why they chose it: Why did they like it, or not. Why was it important or striking? I began with the Boston protests in both classes then discussed some of the ideas in the chapter in the AP classes. The chapter is fairly easy to read because the Morgans were good writers who treat complex ideas and a plethora of facts with great clarity. It is exciting for the students to read such a heavily footnoted piece. It shows the work of historians: quotes that move the story and a reference for each one. AP students got the assignment a week ahead. Of course they all chose sentences and wrote comments under each for homework. The AP students had to upload the sentences to Turnitin.com which resulted in an acceptable 50% plagiarism rate.**** The Regents classes did not have to write the sentences on the board, because the documents were short enough that they could just participate by reading from their documents. The gifted and Regents classes had to hand in their sentences at the beginning of the period.

To begin the class, I ask for questions or comments from the students. They might be struck by the violence of the demonstrations for example. The students might be surprised that these white people were threatening to kill Mr. Oliver or Lt. Governor Hutchinson. These are interesting questions, especially when we begin to see what actually took place. Some of them might comment on the statement from Gov. Bernard that the “Virginia Resolves were an Alarm Bell to the disaffected.” They had previously studied those resolves, see elsewhere on this site the article on Teaching the Virginia Resolves. The last two resolves especially were radical enough and heightened the serious nature of the demonstrations. (The key words of the last two were a refusal to obey the tax and that anyone who passed a tax who was not the Assembly was and enemy to the people of Virginia.) What is an effigy? Someone might very well figure out what that was. There is a label on the doll, Gov Bernard stated. In the course of the discussion I comment that it is white people's voodoo, which always brings a laugh from the mixture of Caribbean, Black Asian and white students in my classes. After a few minutes of general discussion, we can get to an aim.

It is usually easier to use a straight forward aim.

What question can we ask about the demonstrations and the Stamp Act?

Aim: How did the colonists in Boston protest against the Stamp Act?

Two

Before we start talking about the documents in depth, it is important to figure out how the Stamp Act was supposed to operate. I tell the students that the Stamp Act was passed on March 22, 1765 and was supposed to go into effect on November 1. The stamped paper was supposed to come from Britain to the Stamp Distributor. He then sold stamps to the city and provincial governments to use for licenses and to newspaper vendors or people who sold playing cards or dice. Then when a colonist bought a newspaper he would pay for the stamp and the newspaper. Thus the Distributor would get his payment for the job from his initial sale to the vendor or the city government and the vendor or the city government would get paid back for the stamped paper by the customer or the colonist obtaining a lease, a mortgage or a marriage license. I had the students play this out in class to make it clear. I would get three students in the third seat in the third fourth and fifth rows to be the vendor, the customer and the distributor. They could do this in their seats when they were sitting next to each other. There is no necessity for them to stand up. Then the distributor would sell a stamp to the newspaper vendor and then the vendor would sell the stamp and the newspaper to the customer. It was a direct tax on the customer in the end. Then I tell them that the stamped paper had not yet arrived in any of the colonies when the demonstrations began. So, why were the riots so violent? What were the demonstrators trying to accomplish? The students soon figure out that the purpose was to make Mr. Oliver and the other Distributors resign their posts and refuse the stamps before they arrived. In order to enforce the resignation, the Distributor had to resign and refuse in front of the crowd – in public. Now we are ready to discuss the documents.

As the students make their comments based on their reading, or their sentences you should be sure to ask them where they got the information. The documents are divided into pages with right and left columns in both. Ask them to tell you which page which column and which paragraph by identifying the first word of the paragraph and have the students read the passage. Make sure they read slowly and that the rest of the class reads along with them. As they give information or ideas write some of them on the board in groups. Then ask for labels for the groups as the information fills out. The groups can be divided into categories such as 1. The story of the effigy. 2. Examples of violence. 3. Threats by the colonists. 4. Reactions of the authorities. 5. Attempts to stop the demonstrations. 6. Are the demonstrators a Crowd or mob? See above in the description of Charivari.

Three

The Story of the Effigy The great historian Natalie Zemon Davis once wrote that history is a foreign country: So it is always necessary to have a firm grasp on the obvious: why did Gov. Bernard and Lt. Gov. Hutchinson write letters? The demonstrators hung an effigy on a tree in the Boston at the break of dawn. It had an inscription saying it was Mr. Oliver, the man appointed to distribute the stamps in Boston. They left it there all day and protected it from the authorities. In the evening they carried it to the building that was almost finished that Mr. Oliver had built to let out for shops – that is to rent. They called this the “Stamp Office.” They pulled it down in five minutes. This was a wooden building with a second floor window which fire fighters could pull down to prevent the spread of the flames, using fire hooks on the bottom frame. It came apart easily and they carried the wood to near Mr. Oliver's house, cut off the head of the effigy and threw the whole effigy into the fire made from the wood of his building. Readers often misinterpret this story thinking that they had burned down the “Stamp Office.” This is a scary story nevertheless. Mr. Oliver resigned his office the next day in front of the demonstrators and wrote a letter to London to make it official.

Examples of Violence. The demonstrators pulled down the “Stamp Office” breaking all the windows near the street on the way to Fort Hill where they had burned the effigy. They broke Oliver's garden fence and got into the house running around trying to find him. He was not there. They went outside, saw Hutchinson and threw stones at him. Lt. Governor Hutchinson's house was torn apart so that all the covering or wainscoting, was taken off the walls and his paintings and books were stolen or torn apart and most of his furniture was taken apart also. Public papers were taken or destroyed. They cut down his trees, took apart his roof and knocked down partition walls inside. He had no clothes to wear for the next day. Some of the clothes and books were returned to him later. The demonstrators attacked his house because they thought he supported the Stamp Act, which turned out not to be true, he had tried to convince the British not to pass it, but he opposed the action in the streets, as you see.

AP "Contagion" notes on Violence The violence in the chapter 9 is not actually the most prominent aspect of the discussion by the Morgans. Students will come up with some interesting points that are not in the initial two documents about Mr. Oliver and Lt. Governor Hutchinson. On p. 147 They destroyed telescopes and other delicate equipment then threw books down a well. When the demonstrators confronted the friends of the Distributor in Newport they carried off some things from the house, but left when his friends assured them that the Distributor, Augustus Johnson would resign the next day, they left. They went around in a circle to other houses tearing up roofs in some places and floors, and trees in others.

Threats by the Demonstrators The colonists threatened to kill Oliver when they were in his house. They also threatened to kill Hutchinson. Hutchinson told his daughters to leave saying he would protect the property by waiting inside. His eldest daughter returned telling him she would not leave unless he went with her. Later his daughters were very frightened and went to the “castle” to be safe. The demonstrators passed the Council when it was in session and gave three Huzzahs which are angry cheers or cheers of celebration of their actions to intimidate the members of the Council.

AP "Contagion" on Threats There was a threat to the Collector of Newport that succeeded in preventing ships from leaving or entering the port because of the lack of stamped paper p.151. The threats seemed severe, but they were never carried out. The demonstrators succeeded in stopping nearly all the ships from entering or leaving Newport since the Collector, John Robinson, was unable to get the stamps he needed because they were on a man of war. Finally Robinson began allowing the ships to enter and leave without stamps by November 25. The Distributor for Georgia pp.156-57 was in England when he was appointed. The Governor had a special ship take him and he signed the papers and took the oath of office. He distributed the stamps to some subordinates, but quickly found out he was in trouble and he ran off to "parts unknown."

Reactions of the Authorities Some of the Council of the government thought it was just a “boyish sport” and that it would die away. Others said that it could grow worse and something had to be done. Yet others said it was already dangerous. The Council did not want to write anything about this series of incidents. The governor could not get the Council to pass a resolution for peace, but he did write to get the Colonel of the regiment to beat an alarm so there was a record of his concern. All the reporting shows how frightened the authorities were - except for those who hoped it would just go away by itself.

Descriptions of Attempts to Stop the Demonstrations There are 4 places in the Governor Bernard letter that describe attempts to stop the destruction of property. In the morning some of the neighbors wanted to take down the effigy, but they were told it would not be permitted. The the Governor received a message from the Sheriff that some of his men tried to take down the effigy, but did not because they felt their lives would be in danger. The Council could write an order, but it would have been more form than content. Finally on page 108 at the end above the letter from Lt. Governor Hutchinson, Bernard wrote:" I should have mentioned before, that I sent a written order to the Colonel of the Regiment of Militia to beat an alarm; He answered that it would signify nothing, for as soon as the drum was heard, the drummer would be knocked down and the drum broke; he added that probably all the drummers of the regiment were in the Mob. Nothing more being to be done The Mob were left to disperse at their own Time, which they did about 12 o'clock." As you see there were no police. The drummer would have called a posse comitatus (as in cowboy movies) to go after the perpetrators, but it could do nothing in this situation.

Were the Demonstrators a Crowd or a Mob? The Governor called the demonstrators a mob and the title of the documents #38 and #39 were The Riot of August 14th and 26th. It is to be expected that the upper class would use that kind of language for the common people who were in the streets. It is important to note that no matter how many times Mr. Oliver or Hutchinson were threatened with violence the people never laid a hand on them. They always seemed to be warned and got away. If the demonstrators had wanted to kill them they would have done it. It is evident that no matter what they were saying and yelling, they did not want to carry out the threat of murther. The members of the Council who took the problem seriously stated that it was a "pre-concerted business" which means that it was planned. So now it is possible to consider the question of whether the demonstrators were a mob or a crowd.

Four

In the January 6, 2021 insurrection the men and women who attacked the Capitol killed police officers and were only prevented from hanging Vice President Mike Pence by Eugene Goodman, a courageous and very experienced member of the Capitol Police who later won the Congressional Medal of Honor and became the Sargeant at Arms of Congress. Besides that, the Capitol rioters carried weapons, were wearing helmets and body armor and carried bear spray and plastic ties for hand cuffs. That no one was killed in the Boston demonstrations or any of the other Stamp Act demonstrations demarcates the January 6 riot from the crowd action of 1765. It was not an accident that no one was killed. In 1765 it was not war. For the capitol insurrectionists it was war, for a substantial minority of them. The question of what is a crowd versus a mob is worth discussing at the end of the class. A mob is violent, but does not stop at property they also go after people. The crowd in Boston was also violent, but did not attack people -- no matter how much they threatened to do just that. There was organization in both January 6 and in Boston, but the goals were quite different. The Boston crowd's goal was to force the Stamp Distributor to resign his post, whereas the January 6 rioters were trying to overturn the election and expected to have to fight with weapons to enter the Capitol.

AP "Contagion" Notes on Crowd vs Mob On page 146 In Newport Rhode Island a man named Samuel Crandall, walked up to the Customs officer, John Robinson who had somehow offended him and grabbed him by the collar. Robinson and his companions pried him loose and Robinson made his escape. His companion, Mr. Howard, whose effigy hung from a tree in the town began lecturing the crowd that gathered. He soon paid for his actions when a group of men went to Howard's house and tore it apart the way they had done to Hutchinson's in Boston. No murther there. Similarly on p. 155 in Virginia Governor Fauquier and his council were sitting at a coffee house when George Mercer, the man appointed to be Distributor, came by and consulted with the men and the officials. The group of men who had been looking for Mercer were angry that the Council treated him so warmly prepared to seize him. The Governor took him by the arm and walked him safely through the crowd. By the next morning Mr. Mercer had resigned his post. Another case of verbal, but not physical attack. In New York James McEvers resigned with out any pressure after hearing what had happened to Oliver and Hutchinson. And so it was with many of the other Distributors. There was no need of violence only the threats were enough after the experience in Boston and in Newport where there were ships in the harbor to escape to if you were a Distributor or a customs collector you escaped to a ship. Sometimes the crowd did damage to your house, but often the threat was enough. Most of the Distributors were Americans who had much to lose if the crowd were to take apart you house. Augustus Johnson escaped to a ship, but the protesters went to his house and began the work of taking it apart, but left to make sure there was enough to work on if he did not resign. This shows strategic restraint. There is one more key point on the question of the mob or crowd. The demonstrators called themselves "the respectable populace." When this comes up I tell the class that you can just hear Michael Caine saying that in his cockney accent. They did not call themselves a mob, of course. They were fighting for their rights as Englishmen. See page 151.

There is an additional question we must consider. Was the the demonstration in Boston legal? Then how shall we look at this? What justification is there then? They took control of the streets to assert their rights of self - taxation as Englishmen. They had a moral right. This might come up in the initial discussion as the class begins or during the discussion of all the other issues. It is certainly something important to consider. Was it justified, therefore?

AP Notes on Contagion Why was the chapter called "Contagion?" If I have to ask that question, I sneeze. Achoo! Then there is a reference to an "infection" spreading but not north of New Hampshire or south of Georgia p, 157. Hmm. Then there is the last sentence in the chapter:

Boston and Rhode Island could take credit for the initial leadership, but the people in South Carolina, and for that matter in the other colonies could scarcely have been ready to follow such distant leaders if the direction of march had not been agreeable.

Now we are ready to conclude.

Aim: How did the colonists in Boston protest against the Stamp Act?

Conclusion: The Loyal Nine organized a group of mechanics and laborers to intimidate the Mr. Oliver who had been appointed Distributor of the stamped paper that was to come from London. By pulling down his new building and attacking his house they forced him to resign his position. These resignations happened up and down the Atlantic coast in all the colonies that later participated in the American Revolution.

This lesson turns out to be very timely in light not only of the BLM demonstrations, but also in light of the January 6th insurrection. Leaving the discussion open ended in terms of mob or crowd is a good idea. Even when I taught this between the middle 80s and until 2017 I never insisted on one answer or the other. This lesson is fun. The students are excited by the documents and the process of learning how history is actually written. It is the basis of everything we do.

**

***

*

**** See my explanation of the Tarzan theory of reading in “African Slavery in America” elsewhere on this site.

***** Those of you who are teaching American History now can look at On Teaching All Men Are Created Equal elsewhere on this site. It is a series of lessons on the Declaration of Independence. It was also published on History News Network in two parts