Why did Justice John Marshall Harlan Call the Constitution Color-Blind?

Why Did Justice Harlan Call the Constitution Color-Blind?

A Student Led-Lesson by Jeff Schneider

I followed the explanations in the majority opinions and dissents and in the comments by experts from academia and in the news about the recent Supreme Court case Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, and University of North Carolina, as I am sure that my readers have. These arguments about whether the Constitution is “ color-blind” brought me right back to my first chance to teach Plessy v. Ferguson in a high school government class. The rebuttal by Justice Harlan, though problematic, was an explosion that blew Brown’s bald racist opinion out of the murky polluted water his argument was drowning in. The clash reminded me of the long history of endemic and virulent racism in our country and the valiant attempts to counter it by the champions of civil rights. Reading the full opinions in the 1896 case and the opinions from both sides of the Students for Fair Admissions case only added more confirmation that white supremacy was still the serpent feeding at the breast of our democracy, as Frederick Douglass called slavery in 1852. This insight compelled me to analyze the details of Plessy v. Ferguson to show that the the racist and patently false, and disingenuous arguments that constitute the connecting tissue and the very blood of the Opinion of the Plessy Court have maintained their Dred Scott-like power in the majority opinions of the students' case in 2023. It all depended on color. We shall see that Harlan’s characterization of the Constitution as color-blind was the perfect rebuttal to the only “fact” in the Opinion of the Court. Plessy was black.

Just to indicate the depth of the racism and slipshod nature of the the majority opinions in the Roberts court, how could the Chief Justice and all the concurring opinions ignore the voluminous studies proving the effects of racism on Black students discussed by Justice Sotomayor? Where did they question that the students’ organization had real standing since no one who sued had been injured by the admissions practices of Harvard or the University of North Carolina, the respondents in the case? Where did the Chief Justice refute the studies by David Card of Berkeley who showed that Harvard did not discriminate against Asian students? He ignored it in the Syllabus and accepted the plaintiff's argument without the slightest acknowledgement of the controversy.

These justices in the 2023 majority are not truth tellers. (1) They are the enemies of liberty as Justice Harlan implied about Justice Henry Billings Brown, author of the Opinion of the Court in Plessy. See below in the analysis of Paragraph 38 in the Harlan dissent.

Part I Introduction to the Lesson

First we have to investigate the arguments in the Plessy v. Ferguson case. In my classes in the American History survey in high school and college I used an edited version of the opinions by Justice Henry Billings Brown and Justice John Marshall Harlan that enabled me to confine the discussion to one class period. You can download the seven page version of the case here. (2) I followed the procedure explained in “The Tarzan Theory of Reading” explored elsewhere on this site. (3) I should point out that for shorter documents and for AP, gifted classes and average students who had experience choosing sentences from a document, it is not necessary for them to write the sentences they choose on the blackboard. With experience the less advanced students readily volunteer sentences without having to write them on the blackboard.

The assignment for the class was to write an identification of the Plessy v. Ferguson case including the story of the actions Homer Plessy took for which he was arrested, and an ID of the Slaughterhouse Cases (4) which are crucial to understanding the beginning of the document. Then they were asked to read the seven page argument and choose five sentences from the Opinion of the Court and five from the dissent: that is one from the beginning, one from the end and three from the middle of each argument. According to my regular Tarzan teaching explained elsewhere they were to react to each sentence by explaining why they chose it. As I have said, they had to underline the sentences in the document, bring it to class and hand in all their sentences and comments on separate sheets of paper at the beginning of the period.

To begin the class I would ask what the students thought of the case, or if they had any questions. Whatever they contributed was fine as long as they could back it up with examples from the document or their knowledge of the Jim Crow laws. The importance of the case would certainly come up in terms of segregation which was codified into federal law by the Plessy decision. Segregation had been local but widespread in many places in the North and all over the South but now it was a nationally enforceable practice until the decision was overturned in 1954 by Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the North it was not a law, de jure, but de facto, a custom, characterized by local housing and mortgage eligibility restrictions in neighborhoods “enforced” by banks and other businesses, like movie theaters, department stores and luncheonettes.

Discriminatory mortgages in the North relied on city maps which were printed with red lines around Black or poor neighborhoods in cities indicating areas the only areas where Blacks or other minorities lived. This approach was consequently called “redlining.” In other cases segregation was enforced by banks in suburban villages and towns which refused to give mortgages to Blacks, Asians, Native Americans, Jews or other ethnic or racial groups. The current discussion provoked by the Students for Fair Admissions decisions have brought up the idea that since the Constitution was “color-blind” universities should not favor minorities in admissions. Surprisingly, as you might know, we shall see that the phrase actually came from the dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan in the Plessy case: He used it to defend Blacks against discrimination. To add to the drama of this case Harlan, the dissenter had been an enslaver.

Part II The Background of the Plessy v. Ferguson Case

Once the general ideas in the case were brought up, we turned to a description of the facts in the case which would come from their homework IDs. Below is a description which a teacher could use to clear up any mistakes in their stories. I asked for a volunteer to explain her ID about the case. The following is a digest of the facts which the students might contribute.

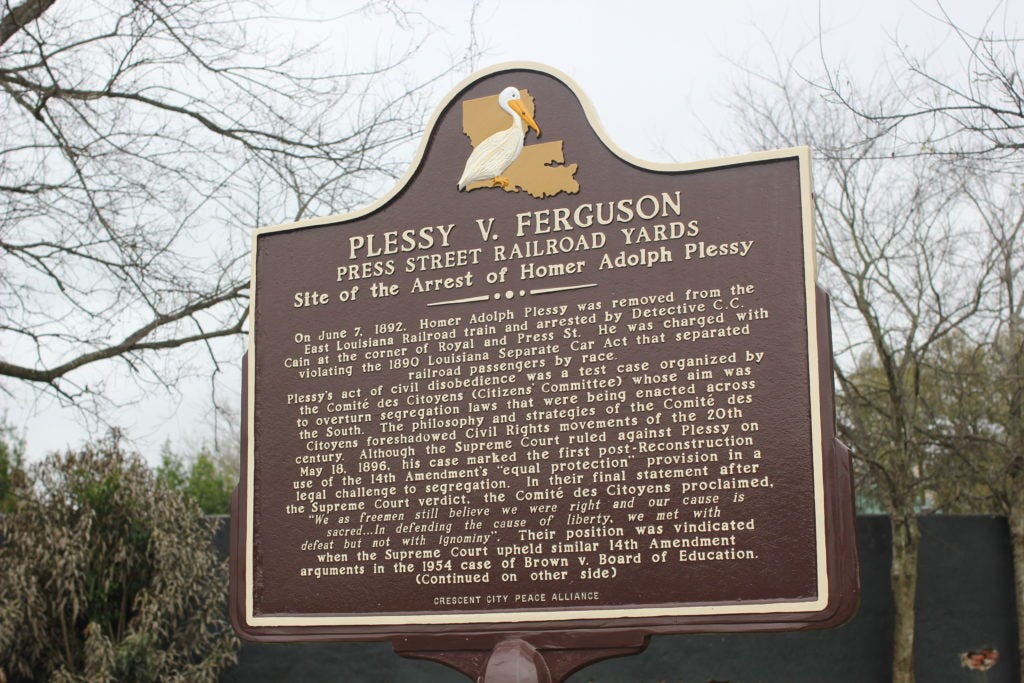

Plessy v. Ferguson was initiated by a the Comi'te des Citoyens (Citizens) of New Orleans to build a legal challenge to the Separate Car Law of the state of Louisiana. The law, passed in 1890 by the Louisiana legislature, stated that passengers traveling on railroads within the state of Louisiana had to sit in separate (but) “equal” cars in a train according to their race. Unless a passenger were, for example, a Black nurse for a white family, all Blacks had to sit in a car for Black people and whites had to sit in a car for whites. Homer Plessy was 1/8 Black but appeared white. As he and fellow committee members had planned, he boarded the train at the nondescript stop in New Orleans that now displays a monument to his case. See below:

The Press St. Stop in New Orleans where Homer Plessy

Boarded the East Louisiana Train

Photo by Jeff Schneider 2017

Historical Marker Plessy v. Ferguson

New Orleans Preservation Center

Plessy bought a ticket on June 7, 1892 for a white first class car and was arrested after the conductor, who was part of the protest organization, asked if he was white. He said “no” but refused to leave the car. Plessy was arrested and taken to the New Orleans Fifth Police Precinct where he was charged with violating the Separate Car Law. Judge Ferguson convicted him in local court in a November trial despite Plessy's plea that the law violated his 13th and 14th Amendment rights. He sued the judge and lost an appeal in the Supreme Court of Louisiana in December 1892. However, he received a certificate of certiorari - asking for a review- that gave him the opportunity to appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. He appealed in 1893 and the Supreme Court took his case in 1896.

Part III The Opinion of the Court by Justice Henry Billings Brown

Now we are ready to start the analysis of the text of the case. I ask if anyone has a sentence from the majority opinion they want to share. The students will see that the arguments and complications of the case appear in a weird combination of stark racism and more obscure racially biased ideas in the majority opinion by Justice Henry Billings Brown. Here are a series of quotations that constitute the core of Brown's argument. We will take a sampling of sentences from the the Opinion of the Court and follow with the dissenting opinion by Justice John Marshall Harlan. Please consult the pdf of the edited case in footnote (2).

The following paragraphs of the Opinion of the Court quoted below constitute an appalling collection of racial fantasies, obscurantist logic and pernicious venom. They are collectively an outstanding example of white supremacist entitlement. Let us go through the argument “thought” by “thought.” In order to tackle this screed in the form of a Supreme Court opinion, I asked only open-ended questions: My extreme characterization above is for the teacher only, I would not use those terms with the students, who should reach their own conclusions. Those characterizations will serve, however, as a thesis for the following analysis. I would ask for the students' sentences and write parts of them on the board as we went through the opinion. Why did you choose this, I would ask.)The capitalization and the spelling are all copied precisely from the original.)

2. The first section of the statute enacts 'that all railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches in this state, shall provide equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored races, by providing two or more passenger coaches for each passenger train, .. No person or persons shall be permitted to occupy seats in coaches, other than the ones assigned to them, on account of the race they belong to.

So if someone chose paragraph 2 they would say that it is a description of the Separate Car Law and is therefore a necessary part of the argument, because it sets the stage for the case. Someone might also point to the prominent use of color in the lines. It is not subtle or attempting to avoid what we would now call discriminatory language. For those not used to reading racist documents it is a shock.

7. The constitutionality of this act is attacked upon the ground that it conflicts both with the thirteenth amendment of the constitution, abolishing slavery, and the fourteenth amendment, which prohibits certain restrictive legislation on the part of the states.

How do you think about Number 7, I ask. The student might choose this because it is the basis of Plessy's law suit. It is important that the students understand that it is his lawyers are arguing against the Separate Car Law using the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution: The defense he raised in his initial objection to his arrest four years before. In the course of the lesson the word plaintiff might come up. It is the legal term for the one who brings the complaint, Homer Plessy.

10. That it does not conflict with the thirteenth amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, is too clear for argument. ...A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races—a distinction which is founded in the color of the two races, and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color—has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races, or re-establish a state of involuntary servitude.

Someone might choose paragraph 10 because it brings up the difference of Black and white people and asserts that it is a legal distinction. The student response might come in the form of a question, why is skin color a legal distinction? The ensuing discussion might remain with this question unanswered or left for later. This statement certainly is peculiar. The paragraph begins, however, with the denial that the case has anything to do with slavery, which seems reasonable enough, but the use of color, very important in the Separate Car Law, seems to be raised in a way that begs for an explanation, a student might say. The tendentious assertion that the distinction of color between the two races “will always exist” is an attempt to deny that it matters at all beyond the superficial difference of pigmentation, but it is understood to carry apparently important, unstated differences that constitute “legal” categories of black and white. The opinion claims that the color difference between Blacks and whites does not constitute or has no “tendency to destroy” inequality between the races. Why then is it raised, someone might ask. We have stepped into a world of reasoning totally unfamiliar to us in 2023. The use of the phrase “involuntary servitude” comes from the 13th Amendment.

12. By the fourteenth amendment, all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are made citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside; and the states are forbidden from making or enforcing any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, or shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or deny to any person within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Paragraph 12 quoted above is a nearly direct quote of the 14th amendment. A student might say that since it is fundamental for Plessy's argument, Justice Brown must analyze it. How do you understand this, I ask. It says that every citizen, born or naturalized has the same rights and privileges before the law that is, in court before a judge. Every citizen of the US is simultaneously a citizen of the state where he resides, and no citizen shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law (a proper trial), and no state shall deny a citizen the equal protection of the laws. Can you make comments about these provisions, I ask. Someone will say that these are civil rights like equality because they are protected by the government. Some of them are based on natural rights mentioned in the Declaration of Independence: life and liberty, but they are guarantees of protection from discrimination by the states. Finally someone might know that the provision that the anyone who is a citizen of the United States was also “a citizen or the state wherein he resides” is a clear reference to the Dred Scott Case of 1857, in which the majority claimed that Blacks were so far inferior and had “no rights which a white man was bound to respect.” As a result Mr. Scott was not a citizen of the state of Missouri or of the United States. Historians have included the Dred Scott Case as one of the causes of the Civil War.

Further, a student might explain that the 14th amendment was passed because after the Civil War the former Confederate states passed laws called Black Codes which deprived the freedmen of the rights to leave a job without permission from the boss, carry a gun, sue, serve on juries or testify in court. These laws were passed by the former Confederate states in 1866 to try to maintain the freedmen in a condition close to slavery, which prompted the Republicans to embark on the new era we now call Congressional Reconstruction. Congress passed a Civil Rights Bill which protected those rights and overrode President Andrew Johnson's veto. Then Congress passed the the 14th Amendment which used essentially the same language as the Civil Rights Bill and required those states to pass the 14th Amendment in 1868 in order to rejoin the Union. As a result of the Reconstruction Act those states were under military control and therefore had no independent governmental structure.

How do you interpret the provisions of the 14th Amendment, I ask. A student might point out that in relation to Plessy's law suit it seems plain that the Separate Car Law of Louisiana is unconstitutional. Every person has the rights of life and liberty and cannot be deprived of those rights without a trial. It would seem that Plessy had a very good defense of his right to sit in the white car.

13. The proper construction of this (14th )amendment was first called to the attention of this court in the Slaughter-House Cases, ... which involved, however, not a question of race, but one of exclusive privileges. The case did not call for any expression of opinion as to the exact rights it was intended to secure to the colored race, ... to protect from the hostile legislation of the states the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, as distinguished from those of citizens of the states.

Now we are in strange territory. Let us see if we can make sense of this set of ideas. The above paragraph uses the Opinion of the Court in the Slaughterhouse cases of 1873 which was the first Supreme Court case based on the 14th Amendment after its passage in 1868. Are there any words in this quote that you are unfamiliar with, I ask. The students might not understand the word construction which refers to a meaning coming from an interpretation of a sentence. It comes from the word construe or to explain how the words form a meaning. Lines in the Constitution may be construed in different ways. We will now be dealing with constructions of the 14th Amendment.

The students will give the background of the case from their homework, which concerned a law passed in New Orleans to improve sanitation by centralizing all the butchering of meat in one place for the whole city. Two groups of butchers brought a law- suit protesting that the city was forming a monopoly which ignored their rights as protected under the 13th and 14th Amendments: They had places of work which could no longer be used legally. This argument, as understood by the 1873 majority, was that the case “ was not a question of race,” but was about the rights of the butchers who opposed the new law that gave the city the right to deprive them of their livelihood by creating corporation with exclusive privileges (a monopoly) in a single place in the city, where all the butchers would have to work.

How do you understand Justice Brown's comment on the 14th Amendment I ask. It is not clear from the sentence, but perhaps someone read an analysis or could guess that the butchers were white, which Justice Miller neglects to mention at any point in his opinion as writer of the Opinion of the Court. The Slaughterhouse Cases were decided against the white butchers because the white men of New Orleans had no 14th Amendment protection from state legislation and the monopoly was a legal corporation to which they had no right to object. In order to unpack this quote from Plessy v. Ferguson in paragraph 13, let us take a look at some quotes from the Opinion of the Court in the Slaughterhouse Cases to understand where Brown found the foundations of his reasoning.

p.73 (A)ll the negro race who had recently been made freemen, (in 1865 by the 13th Amendment) were still, not only not citizens, but were in-capable of becoming so by anything short of an amendment to the Constitution.To remove this difficulty primarily, and to establish a clear and comprehensive definition of citizenship which should declare what should constitute citizenship of the United States, and also citizenship of a State, the first clause of the first section was framed.

How do you interpret this statement, I ask. It is clear that the 14th Amendment applies to the Black people who had been deprived of citizenship by the Dred Scott decision. But the citizenship is divided between the United States and the states in which the freedmen reside. Where is he going with this, you may ask?

p.73 All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."...It declares (Justice Miller explained) that persons may be citizens of the United States without regard to their citizenship of a particular State, and it overturns the Dred Scott decision by making all persons born within the United States and subject to its jurisdiction citizens of the United States. That its main purpose was to establish the citizenship of the negro can admit of no doubt. The next observation is more important in view of the arguments of counsel in the present case. It is, that the distinction between citizenship of the United States and citizenship of a State is clearly recognized and established.

How do you understand these statements, I ask. Are there differences between being a citizen of a state as opposed to a citizen of the United States? Does the 14th Amendment say there are differences, students may ask. We will set this aside for a moment. It is clear from the plain words of the amendment that securing the rights of Blacks was its primary purpose. Now we must confront the following:

p.74 The argument, however, in favor of the plaintiffs (the white butchers) rests wholly on the assumption that the citizenship is the same, and the privileges and immunities guaranteed by the clause are the same. ( In both the US and the states) The language is, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States." It is a little remarkable, if this clause was intended as a protection to the citizen of a State against the legislative power of his own State, that the word citizen of the State should be left out when it is so carefully used, and used in contradistinction to citizens of the United States, in the very sentence which precedes it.... (W)e wish to state here that it is only the (citizenship in the United States) which are placed by this clause under the protection of the Federal Constitution, and that the rights of (the citizens of the states), whatever they may be, are not intended to have any additional protection by this paragraph of the amendment.

How do you understand this parsing of the sentence, I ask. The students will say that Justice Miller in the majority opinion in the Slaughterhouse Cases claimed there were differences between federal and state rights. First he claims that the sentence includes only federal rights and excludes state rights because the amendment left out a second iteration of the clause “and the states wherein they reside.” Huh? As the students will see, despite the proper statement of the protections of the 14th Amendment “can admit of no doubt” that these words applied to the freedmen's rights of citizenship in the United States, not the states. How is he going to use that, the students might ask.

p.77 Was it the purpose of the fourteenth amendment, by the simple declaration that no State should make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, to transfer the security and protection of all the civil rights which we have mentioned, from the States to the Federal government? And where it's declared that Congress shall have the power to enforce that article, was it intended to bring within the power of congress the entire domain of civil rights heretofore belonging exclusively to the States?

How would you interpret that, I ask. The students will come to the conclusion that the answer to Justice Miller's question should be: Yes! The Reconstruction Acts that reduced the 11 confederate states to 5 territories plus Tennessee and forcing them to pass the 13th 14th and 15th Amendments was clearly designed to change the the local laws not only granting the Blacks civil rights but also the right to vote, serve on juries, and sue in court. It was designed to change the relationships between the federal government and the states. The reading of the 14th Amendment in Miller's “state rights” point of view (a 19th century expression) guts the protections of equality before the law, or any other of the rights protected in the plain words of the Civil Rights amendment.

p.78 (S)uch a construction followed by the reversal of the judgments of the Supreme Court of Louisiana in these cases, (ruling in favor of the butchers) would constitute this court a perpetual censor upon all legislation of the States, on the civil rights of their own citizens, ... when the effect is to fetter and degrade the State governments by subjecting them to the control of Congress, in the exercise of powers heretofore universally conceded to them; ...when in fact it radically changes the whole theory of the relations of the State and Federal governments to each other and of both these governments to the people; ... We are convinced that no such results were intended by the Congress which proposed these amendments, nor by the legislatures of the States which ratified them.

How do you understand this passage, I ask. The students will point out that Justice Miller has confirmed our reading that the majority of the court has taken the 14th Amendment to mean exactly the opposite of the way it was written. He has elevated state rights over the federal Constitution and denied the rights to the butchers by splitting the rights of the citizens of the United States from the rights of those same citizens who are simultaneously living in the United States in the state of Louisiana. In response take into consideration the following quote from one of the three dissents in the Slaughterhouse Cases. It is written by Justice Noah Swayne:

p.126 (1.) Citizens of the States and of the United States are defined.

(2.) It is declared that no State shall, by law, abridge the privileges or imunities of citizens of the United States.

(3.) That no State shall deprive any person, whether a citizen or not, of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. A citizen of a State is ipso facto a citizen of the United States.

How do you understand this, I ask. Is there a phrase you do not know in this quote? Ipso facto is a Latin phrase that means by that very fact, as an inevitable result of the words themselves or automatically. One of the students might say that it is about time! We all need a break from the distressing readings of the Miller opinion. The quote is in a rough form of a syllogism, a three-part proof in logic. The students will conclude that he has taken apart the majority opinion in just a few words. The idea that you can misunderstand the words of the 14th Amendment by claiming that the citizens of the US can be deprived the the rights that had just been granted in the first sentence to the citizens of the state “wherein they reside” is both appalling and ridiculous.

Here is our final quote from the Slaughterhouse Cases listing many of the rights of the citizens of the United States. To wit:

p.79 (W)e venture to suggest some (rights)which owe their existence to the Federal government, its National character, its Constitution, or its laws. ... It is said to be the right of the citizen of this great country, protected by implied guarantees of its Constitution, to come to the seat of government to assert any claim he may have upon that government, to transact any business he may have with it, to seek its protection, to share its offices, to engage in administering its functions. He has the right of free access to its seaports, through which all operations of foreign commerce are conducted, to the subtreasuries, land offices, and courts of justice in the several States....

The students will notice that none of the rights, liberties and privileges listed in the 14th Amendment are in this paragraph. The right to equality in your daily life “in the state wherein you reside” is not mentioned because the citizenship in the United States excludes the power over the individual states according to the tortured reasoning of Justice Miller. We are forced to conclude that no one, Black or white, has 14th Amendment rights according to this reasoning. Now we are ready to continue with the argument in by Justice Brown in Plessy v. Ferguson.

13. The object of the ( 14th ) amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but, in the nature of things, it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either. Laws permitting, and even requiring, their separation, in places where they are liable to be brought into contact, do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other, and have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within the competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of their police power. The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children,...

If a student chooses a sentence in paragraph 13, they will immediately see that Brown has acknowledged the true nature of the 14th Amendment but there are supposedly mitigating circumstances concerning “color” that have come right back into the argument. Are there any words that are unfamiliar to you, I ask. Commingling refers to mixing of races. The term police power refers to laws that are enforceable by the state, city or federal government. Someone might say that Brown has gone from differences between Black and white people as a distinction of color to a legal category of a color difference. Now he is going from a difference of color to a question of social as opposed to political separation with a second denial of inferiority. He does not say that Blacks are inferior, but there are social not political distinctions based on color The laws that separate the children by race in schools are mentioned here, but he is denying or at least not insisting on inferiority, Someone might point out that in the Slaughterhouse Cases the question of state law also came up in relation to the 14th Amendment. In the Slaughterhouse majority opinion Miller concentrated on the white butchers, to whom he denied the protection of the 14th Amendment rights and privileges claiming it only referred to Black people and was, written for the equality their protection, not the whites. Now Brown is denying the protection of the 14th Amendment to the Blacks, the supposed primary subject of the change to the Constitution in 1868 when the amendment went into effect.

Furthermore, that distinction between state and federal mentioned in paragraph 13 extended into nearly all the quotes in the previous analysis of the Slaughterhouse Cases opinion is a key point of discussion. The students will conclude that Brown gave it a different emphasis: It was the tradition of the separation of the races Brown emphasizes here, not only the rights of the citizens of the United States. He is insisting, as Miller did, that the state should control the rights of the Blacks by separating the races. “It could not been intended” to force a social commingling of the races. it seems. The undoing of the 14th Amendment discussed above in the Slaughterhouse Cases had similar assumptions. Brown is appealing to the folkways of the South which include strict segregation of the races. It recalls our discussion of the right of Congress to control the local laws of the states. It is clear that the phrase “unsatisfactory to the other” when discussing commingling is problematic. In the ensuing discussion many questions could arise. Why would they be unsatisfactory to the other? Would both races feel the same way or are they expected to feel uncomfortable? Is there a threat of violence in these words? Are these segregation laws meant to prevent conflict or is conflict being encouraged or assumed?

The students will also conclude that Brown has raised another distinction: between political and social. It could not have been intended “to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality.” He is implying that political equality can be enforced, but not social equality. All these ideas are implied in the quote above. We shall set these ideas aside for the moment because they will arise more clearly in the very last paragraph of the majority argument.

Before we leave Brown's argument, however, I cannot resist the temptation to point to the following in paragraph 22. To wit:

22. It is claimed by the plaintiff in error that, in a mixed community, the reputation of belonging to the dominant race, in this instance the white race, is 'property,' in the same sense that a right of action or of inheritance is property. Conceding this to be so, for the purposes of this case, we are unable to see how this statute deprives him of, or in any way affects his right to, such property. If he be a white man, and assigned to a colored coach, he may have his action for damages against the company for being deprived of his so-called 'property.' Upon the other hand, if he be a colored man, and be so assigned, he has been deprived of no property, since he is not lawfully entitled to the reputation of being a white man.

Are there any words here that you are unfamiliar with? The plaintiff in error is Plessy who is taking his case to the Supreme Court because he claims that the Louisiana supreme court was in error. How would you interpret number 22, I ask. Students will be shocked by the bold assumption of that whites would have rights and privileges that would “obviously” be denied to Blacks, because they have no rights which a white man is bound to respect, to coin a phrase. The students will conclude that the superiority of the white men is a given, unquestioned. It is an example of racism so extreme: it is white supremacy to the last possible degree. Someone might say that the comparison could be reversed: a white man is not lawfully entitled to the reputation of being a Black man! Like Frederick Douglass or W.E.B. DuBois for example.

24. So far, then, as a conflict with the fourteenth amendment is concerned, the case reduces itself to the question whether the statute of Louisiana is a reasonable regulation, ... In determining the question of reasonableness, it is at liberty to act with reference to the established usages, customs, and traditions of the people, and with a view to the promotion of their comfort, and the preservation of the public peace and good order. Gauged by this standard, we cannot say that a law which authorizes or even requires the separation of the two races in public conveyances is unreasonable, or more obnoxious to the fourteenth amendment than the acts of congress requiring separate schools for colored children in the District of Columbia, ...

How do you interpret paragraph 24, I ask. The students will conclude that its language above implies danger and violence much more than reasonableness. The folkways of the South, their traditions, are based on enforced order through separation. The hidden tension of segregation that M. L. King Jr. refers to in the Letter from Birmingham Jail is the basis of the relations between whites and Blacks in the South in 1896. It is clear that Brown believes segregation is the mechanism that keeps the peace between the races. The dangers of race conflict are close to surface at all times. He is relying on the tradition of school segregation to which he doubts anyone could object. So he has argued that even if the 14th Amendment could be interpreted as granting equality to Blacks in the Louisiana railroad cars (see paragraph 23), such a conclusion is unreasonable because the mechanisms of separation are the South's peculiar tradition and must be upheld for reasons of safety and as well as honoring longtime and valued custom. Justice Brown has made a plea for the maintenance of the veneer of the genteel folkways of the racist South.

And now we have come to the paragraph which ties Brown's argument together:

25. We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it. ...The argument also assumes that social prejudices may be overcome by legislation, and that equal rights cannot be secured to the negro except by an enforced commingling of the two races. We cannot accept this proposition. If the two races are to meet upon terms of social equality, it must be the result of natural affinities, a mutual appreciation of each other's merits, and a voluntary consent of individuals. Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts, or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane...

This section is quite a challenge. How do you interpret it, I ask. Are there any words here that you are unfamiliar with? Natural affinities mean mutual attractions, the phrase is akin to elective affinities, originally a used for the attraction between a metal and a nonmetal in chemistry. The students will conclude that Brown is blaming the Blacks for feeling inferior. The whites are guiltless in this situation. That Blacks and whites are separated is a neutral act. It is “only” the tradition of the South. The Separate Car Law does not say that Blacks are inferior. They nevertheless might feel inferior though Brown has only raised that in the subjunctive. See paragraph 25 above. Then Brown takes up social prejudices - a new word in this nit-picking “treatise.” He says the plaintiff assumes that social prejudices may be overcome by legislation: that is what William Graham Sumner later called the folkways (traditions of the South) may be overcome by stateways (force or police power or laws passed by government). The conservative political phrase “folkways versus stateways” is ingrained in Southern culture and discourse. It is what the Southerners later claimed was the reason for opposing civil rights legislation for the whole first half of the 20th century. It is the difference between “changing hearts and minds first” and “Freedom Now!”

There are a series of parallel arguments here. There is a threat of violence because of racial instincts. Racial instincts come to the surface if whites and Blacks commingle. So whites and Blacks cannot share a railroad car.

Social prejudices can only be overcome by natural affinities and voluntary consent because racial instincts (the quiet part) cannot cannot be eradicated or abolished by legislation. because they depend on physical differences. That is, he identifies unchangeable physical differences as the root of inferiority. All that we have set aside in the quotations above comes into play here. Brown has identified social differences creating a feeling of inferiority in the Black people with the one thing no one can deny: the color of the Black people, their physical differences from whites. He has labelled color a legal distinction and separated it from the political rights described in the 14th Amendment. Neither racial instincts nor skin color can be changed by political laws. They are separate realms: first the social inferior feeling by Blacks then the implied irrational racial instincts and second the political promises of the 14th Amendment. Did the congress mean to abolish state control of civil rights in the 14th Amendment? Yes, we said!! But not in Brown's construction. Then he turns to the subjunctive: If!

If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane...

Does Brown say that Blacks are inferior? No. He only implies they might be. Their inferiority inheres in the color of their skin and their feelings of inferiority. Can you separate Blacks from their skin color? They might be entitled to the political or civil rights of the 14th Amendment if the Justice had not taken on the absurd bifurcation between state and federal citizenship, but he will not stand for it, because they have only one body and their color forces them to into separate accommodations on the railroad. They still have political rights as citizens of the United States, but in the state of Louisiana they cannot enjoy them because despite their political selves being equal, their social selves, when sitting next to whites are clearly unworthy. Brown takes the feeling for the fact and uses that to imply that Black people are inferior. If they feel inferior because of social separation then they are, so the Constitution cannot put them on the same plane. But the quiet part is that the purpose of all this is social separation because of the possible effects of racial instincts. Violence is lurking in the possibility of commingling of the races. The implication is that the races must be separated in order to protect them both from the possibility of violence.

In sum Blacks are simultaneously civil, political and social beings. They cannot sit next to whites on the railroad because they are not white and stimulate the racial instincts of both (?) the whites and Blacks. Therefore in social situations Blacks and whites must be separated. Legislation cannot rectify this disparity of color and inferiority if it exists. Since the Blacks are a different color they must be separated because as plain as can be, they are not white. The only incontrovertible and unchangeable fact in Brown's argument is that the Blacks are a different color from whites. It is a true, physical fact.

27. The judgment of the court below is therefore affirmed.

Justice Brown has allowed the judgement against Homer Plessy in the Supreme Court of Louisiana to stand. He was guilty of traveling while black.

Part IV The Dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan

There was only one dissent in the case. We will consider the following quotes from Justice Harlan's opinion.

32. While there may be in Louisiana persons of different races who are not citizens of the United States, the words in the act 'white and colored races' necessarily include all citizens of the United States of both races residing in that state. So that we have before us a state enactment that compels, under penalties, the separation of the two races in railroad passenger coaches, and makes it a crime for a citizen of either race to enter a coach that has been assigned to citizens of the other race....

33. Thus, the state regulates the use of a public highway by citizens of the United States solely upon the basis of race.

34. However apparent the injustice of such legislation may be, we have only to consider whether it is consistent with the constitution of the United States....

If a student chooses any of these sentences, I ask why she chose them. The students will surmise that Justice Harlan is cutting right to the key aspect of the Opinion of the Court: it is based on race. He is clearly concerned with the apparent injustice of the law. A point which Justice Brown spent his whole opinion denying.

36. In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens, the constitution of the United States does not, I think, permit any public authority to know the race of those entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of such rights. Every true man has pride of race, and under appropriate circumstances, when the rights of others, his equals before the law, are not to be affected, it is his privilege to express such pride and to take such action based upon it as to him seems proper. But I deny that any legislative body or judicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens when the civil rights of those citizens are involved. Indeed, such legislation as that here in question is inconsistent not only with that equality of rights which pertains to citizenship, national and state, but with the personal liberty enjoyed by every one within the United States....

What do you notice in paragraph 36, I ask. The racism of the 19th century threatens to come right out in this quote. However, it is a neutral statement about a general pride of race because, at least here, Harlan does not go over the line into a bald discriminatory statement. Instead, he states that the races are equal before the law and which must be respected when anyone asserts himself. He assumes that Blacks also have a pride of race when he says every man, which actually is big step forward from anything that Brown included in his opinion. Rights for all citizens is a welcome change from the Opinion of the Court.

37. The thirteenth amendment does not permit the withholding or the deprivation of any right necessarily inhering in freedom. It not only struck down the institution of slavery as previously existing in the United States, but it prevents the imposition of any burdens or disabilities that constitute badges of slavery or servitude. It decreed universal civil freedom in this country. This court has so adjudged. But, that amendment having been found inadequate to the protection of the rights of those who had been in slavery, it was followed by the fourteenth amendment, which added greatly to the dignity and glory of American citizenship, and to the security of personal liberty, by declaring that 'all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside,' and that 'no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.' These two amendments, if enforced according to their true intent and meaning, will protect all the civil rights that pertain to freedom and citizenship. Finally, and to the end that no citizen should be denied, on account of his race, the privilege of participating in the political control of his country, it was declared by the fifteenth amendment that 'the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.'

How do you interpret paragraph 37, I ask. First, Harlan finds value in the 13th Amendment regarding any implication that the freedmen should be subject to “badges of slavery or servitude” left over from the slave codes or other laws of the Confederate states. Justice Brown had dismissed the 13th out of hand. However Harlan agrees with Brown that the 14th Amendment contained necessary protections but says these “added to the dignity and glory of American citizenship.” unlike Brown. These privileges and immunities and civil rights contained in the actual meaning of the amendment which Brown had tried to obliterate by claiming to find distinctions among the myriads of angels on the heads of constitutional pins. Harlan also draws on the 15th Amendment to his argument which includes the provisions that no citizen shall be denied the right to vote “on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude” by any state or by the United States. It is a pleasure to read such a statement with, you will excuse the expression, its original meaning!

38. These notable additions to the fundamental law were welcomed by the friends of liberty throughout the world. They removed the race line from our governmental systems. They had, as this court has said, a common purpose, namely, to secure 'to a race recently emancipated, a race that through many generations have been held in slavery, all the civil rights that the superior race enjoy.' They declared, in legal effect, this court has further said, 'that the law in the states shall be the same for the black as for the white; that all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws of the states; and in regard to the colored race, for whose protection the amendment was primarily designed, that no discrimination shall be made against them by law because of their color.'

How do you interpret this statement, I ask. The distinction that Justice Brown had been making between United States citizenship and citizenship in the states where Blacks reside does not appear in these sentences. Adding the wording of the 15th Amendment, which prohibited discrimination by race, color or previous condition of servitude concerning the right to vote, has strengthened the argument for equality between the races. Further, he states that such reforms were “welcomed by the friends of liberty” putting the majority opinion in the camp of the enemies of liberty.

40. It was said in argument that the statute of Louisiana does not discriminate against either race, but prescribes a rule applicable alike to white and colored citizens. ... Every one knows that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons. ...The fundamental objection, therefore, to the statute, is that it interferes with the personal freedom of citizens. 'Personal liberty,' it has been well said, 'consists in the power of locomotion, of changing situation, or removing one's person to whatsoever places one's own inclination may direct, without imprisonment or restraint, unless by due course of law.' 1 Bl. Comm. 134.* If a white man and a black man choose to occupy the same public conveyance on a public highway, it is their right to do so; and no government, proceeding alone on grounds of race, can prevent it without infringing the personal liberty of each.

How do you understand the argument in paragraph 40, I ask. The students will conclude that the majority's argument is a thin veneer for discrimination. Justice Brown is pretending that the separate cars are accessible to anyone riding on the railroad when in actuality the law infringes on the personal liberty of Black men to sit where they please, in a car with the whites, on the basis of equal rights in a public place. The quote turns out to be from the famous commentary on the English constitution by William Blackstone written in 1765.*

41. It is one thing for railroad carriers to furnish, or to be required by law to furnish, equal accommodations for all whom they are under a legal duty to carry. It is quite another thing for government to forbid citizens of the white and black races from traveling in the same public conveyance, and to punish officers of railroad companies for permitting persons of the two races to occupy the same passenger coach. ...Further, if this statute of Louisiana is consistent with the personal liberty of citizens, why may not the state require the separation in railroad coaches of native and naturalized citizens of the United States, or of Protestants and Roman Catholics?

42 The answer given at the argument to these questions was that regulations of the kind they suggest would be unreasonable, and could not, therefore, stand before the law. There is a dangerous tendency in these latter days to enlarge the functions of the courts, by means of judicial interference with the will of the people as expressed by the legislature.

In paragraphs 41 and 42 the students will notice that Harlan has predicted the segregation of the Jim Crow South: He takes apart Brown's argument that maintaining the traditions of the Old South is reasonable and points out Brown’s judicial overreach.

43. The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage, and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guarantied by the supreme law of the land are involved. It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race.

How do you react to paragraph 43, I ask. Perhaps there are words in the selection that you are not familiar with. The word caste refers to the system of discrimination that controlled, until recently, life chances in India: Every Hindu child was born into a group that defined life boundaries or advantages from the poorest to the most powerful. The final expositor refers to the Supreme Court, the highest court in the US whose rulings explain or interpret the law for all to follow. The fundamental law of the land is the Constitution which controls the extent of the powers of laws and decides whether they are constitutional.

The students will undoubtedly say that the language in in the first two sentences is offensive. It begins with a white supremacist statement that I am sure, to Justice Harlan, seemed absolutely acceptable, but in 2023 we must criticize the assertions that whites are justifiably dominant over Blacks in our country and always will be. Racism clearly included an expectation that Black people would not read the opinion or perhaps not even be aware of its existence. Even though a group of Black people brought the lawsuit all the way to the Supreme Court and there was a Black lawyer was among the attorneys defending Plessy. However if we cancel Justice Harlan for making that statement we will miss his sophisticated explanation of the proper constitutional relationship between the races in the US since the 13th and 14th Amendments were passed. In our country there is no legal structure that raises whites above Blacks: Everyone is equal before the law. It is the reasoning behind the indictments of Donald Trump, his lawyers and the subpoenas for his adult children. No one is above the law. Students will come to the conclusion that Harlan's statement that the Constitution is color-blind is the centerpiece of the dissent. It is a powerful statement. How will we interpret that phrase, I ask. It has reverberated through the coverage of the students’ affirmative action lawsuit on very platform from print to Twitter. Eventually the students will come to the conclusion that Harlan has undercut the whole majority argument simply by stating that the only truth that Brown has to depend on is that Blacks are not white. If the Constitution cannot see color then there is no factual basis to the Separate Car Law. Absent color there can be no case. for arresting Plessy. What, after all, determines that blacks are inferior? The rest of the conclusion is in the subjunctive. There is no proof in a sentence that is hypothetical. The Constitution is color-blind is a preternaturally powerful statement. Black people are not white. The only difference between Blacks and whites that Brown can point to is the difference of color. As Pallidin said in Have Gun will Travel: “It is always necessary to have a firm grasp of the obvious.” The rest of the argument is assumption on top of assumption. It is like depending on hope against hope If(?) Blacks feel inferior socially when separated from whites, then they must be inferior. Nothing in the law makes them inferior. Then since they are inferior socially then the Constitution cannot raise them to equality. For the sake of racial peace it is necessary to separate the races. Color and instinct do not change. Only natural affinities can change the relations between Blacks and whites. Waiting for the South to eliminate discrimination is, as we know, hopeless.

44. In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.

45 It was adjudged in that case (Dred Scott) that the descendants of Africans who were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, were not included nor intended to be included under the word 'citizens' in the constitution, ...(As we have discussed in # 12 above from the Brown majority opinion.) ... But it seems that we have yet, in some of the states, a dominant race,—a superior class of citizens,—which assumes to regulate the enjoyment of civil rights, common to all citizens, upon the basis of race. The present decision, it may well be apprehended, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficent purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the constitution, by one of which the blacks of this country were made citizens of the United States and of the states in which they respectively reside, and whose privileges and immunities, as citizens, the states are forbidden to abridge. Sixty millions of whites are in no danger from the presence here of eight millions of blacks. The destinies of the two races, in this country, are indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law. What can more certainly arouse race hate, what more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between these races, than state enactments which, in fact, proceed on the ground that colored citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens? That, as all will admit, is the real meaning of such legislation as was enacted in Louisiana.

How do you interpret this, I ask. The students will see that Justice Harlan has welcomed the 14th Amendment and emphasized the ideas that we have discussed above that Brown in advocating separating the races on public conveyances is consciously promoting race hate instead of attempting to mitigate it. What a condemnation to compare Brown's argument to Taney's in Dred Scott! Further, Harlan asserts that “the two races are indissoluably linked together” that in the decision “the seeds of race hate have been planted under the sanction (protection) of law” He characterizes the Brown argument as treating the Blacks as too “degraded” to sit next to whites. These “instincts,” Brown claimed would emerge in social situations and whites and Blacks would lose control and attack each other on the trains. Hate and violence are consequences of the intermingling of the races. Harlan is not letting Brown off the hook. He is justifiably angry. It is absurd that 60 million whites should fear 8 million blacks. It was after all the white Southerners who started the Civil War, not the Blacks.

47 It is scarcely just to say that a colored citizen should not object to occupying a public coach assigned to his own race. He does not object, nor, perhaps, would he object to separate coaches for his race if his rights under the law were recognized. But he does object, and he ought never to cease objecting, that citizens of the white and black races can be adjudged criminals because they sit, or claim the right to sit, in the same public coach on a public highway.

How do you explain paragraph 47, I ask. The students will see that Jusitice Harlan has supported the 1st Amendment rights of free speech and the right to petition the government: The Blacks have the right to protest and “ought never to cease objecting(!)” Would you have expected that a white man, in 1896,a former enslaver himself (!) would say that? Evidently, Harlan took our freedoms seriously.

49. We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with a state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens,—our equals before the law. The thin disguise of 'equal' accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead any one, nor atone for the wrong this day done.

How do you comment on that, I ask. A student might say “Shame on you Henry Billings Brown.” We may point out that so-called American exceptionalism displayed here was a trope in 1896, this American boast has a long history.

52. I am of opinion that the state of Louisiana is inconsistent with the personal liberty of citizens, white and black, in that state, and hostile to both the spirit and letter of the constitution of the United States. If laws of like character should be enacted in the several states of the Union, the effect would be in the highest degree mischievous. Slavery, as an institution tolerated by law, would, it is true, have disappeared from our country; but there would remain a power in the states, by sinister legislation, to interfere with the full enjoyment of the blessings of freedom, to regulate civil rights, common to all citizens, upon the basis of race, and to place in a condition of legal inferiority a large body of American citizens, now constituting a part of the political community, called the 'People of the United States,' for whom, and by whom through representatives, our government is administered. Such a system is inconsistent with the guaranty given by the constitution to each state of a republican form of government, and may be stricken down by congressional action, or by the courts in the discharge of their solemn duty to maintain the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.

Reading these sentences a student might find that Justice Harlan has run the table on the great works of civil rights and democracy. He quotes the Gettysburg Address, “for whom and by whom... our government is administered,” the Preamble to the Constitution “We the People,” to “interfere with the blessings”of freedom and the abolitionist argument based on Article IV: the guarantee to the states of a republican form of government. A republican government refers to control by the people and Article VI is the supremacy clause of the Constitution which grants the powers of protecting our freedom to the Congress and the Supreme Court. He calls the Separate Car Law “sinister legislation,” which means menacing, threatening or dark. But he begins with the personal liberty from the 14th Amendment, one of his most powerful arguments which goes right back the Blackstone, the foremost expositor of the English Constitution.

53. For the reason stated, I am constrained to withhold my assent from the opinion and judgment of the majority.

Justice Harlan dissented.

Now that we have demonstrated in extensive detail the fabrications and tortured logic of the majority in the Plessy case we can acknowledge that the majority of the current Roberts court leaves itself open to similar charges of intellectually fatuous treatment of the facts in the Students for Fair Admissions case. The series of criticisms of the Roberts majority in the Introduction to this article, cursory though they are, indicate a marked disregard for standing, a lack of either an analysis of racism, or of a serious engagement with the extensive research on the actual process of admissions at Harvard. All those were not refuted or even considered in the majority opinions. The current court is showing itself to be a throwback to slipshod practices which were left behind starting with the landmark case that overturned Plessy and led the way to the civil rights revolution in the middle three decades of the 20th century. The methods have been reappearing since the Roberts led the majority in the over turning of Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby v. Holder (2013). These cases including Dobbs v. Jackson (2022) and the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University and Universitry of North Carolina (2023) are literally reactionary decisions taking away rights of long standing which each justice who voted to overturn them falsely claimed during their confirmation hearings they would support as had been common in jurisprudence respecting stare decisis. There is no debate in the majority opinions. Only assertions of positions. Like Justice Brown they start with the conclusions and work backward no matter how tortured the reasoning. Justices Sotomayor and Kagan wrote they overturned them only because they had the votes. Those actions were contrary to the majorities of more than 63% to 76% of Americans.

It is noteworthy that Justices Sonya Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson have dropped the color-blind defense that worked so well for Justice Harlan. The reactionary majorities have begun to use color-blind arguments. As a work-around, they have combined them with free-market, classical liberalism to produce decisions that ignore questions of race discrimination or any conscientious defense of the rights of minorities, labor or women. Free enterprise has taken charge of their intellectual methodology. It is an anything goes excuse to produce conclusions that are invented out of the whole cloth of originalism. They have almost abandoned any defense of voting rights, or the rights of individuals and gone over to defense of business monopolies and government support of religious doctrines both in schools and health care. As we have seen, they have learned well from the obtuse logic of Justice Henry Billings Brown. To wit:

The object of the ( 14th ) amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but, in the nature of things, it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races…

This is a bald-face lie worthy of George Wallace, or Donald Trump or Samuel Alito or…

But to end on an optimistic note. Let us consider the long tradition of dissent that at one time led to the overturning of Plessy and the 2nd Reconstruction of the 1960s and 70s. Having taught the American history survey for more than 30 years, I have discovered the remarkable similarity of the dissents in some of the most troubling cases concerning the rights of minorities from Dred Scott to Plessy to Korematsu. The best ones point to the same documents and express the same sensibilities about the rights of Blacks and immigrants. They take the real meaning of “We the People” as Frederick Douglass did in an 1860 speech in Scotland to which I referred in my analysis of the 4th of July Oration (7)

“(W)e the people not we the white people, not even we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low, but we the people; not the horses and sheep and swine and wheel barrows... but we the human inhabitants; and if the Negroes are people they are included in the benefits for which the Constitution of America was ordained and established.”

But the first was the brilliant dissent by Benjamin Curtis in the 1857 Dred Scott case in which he concluded after reminding his readers that Black people voted in New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New Jersey at the time of the state conventions that ratified the Constitution. He actually proved that Taney was wrong: Free Blacks had rights. Here is an excerpt from his dissent:

The fourth of the fundamental articles of the Confederation was as follows: "The free inhabitants of each of these States, paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice, excepted, shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States." …That the Constitution was ordained and established by the people of the United States, through the action, in each State, of those persons who were qualified by its laws to act thereon, in behalf of themselves and all other citizens of that State. In some of the States, as we have seen, colored persons were among those qualified by law to act on this subject. These colored persons were not only included in the body of "the people of the United States," by whom the Constitution was ordained and established, but in at least five of the States they had the power to act, and doubtless did act, by their suffrages, upon the question of its adoption. It would be strange, if we were to find in that instrument anything which deprived of their citizenship any part of the people of the United States who were among those by whom it was established.

The third example of this constitutional argument comes from the powerful dissent in the Korematsu v. United States, the Japanese internment case in 1944. Justice Frank Murphy wrote:

I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States. All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must, accordingly, be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment, and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.

These statements range from 1857 to 1944, but repeat the same fundamental argument. They are a tribute to the courage of the plaintiffs and the confidence the Justices who wrote them in the freedoms we have won since the words “All Men Are Created Equal” were penned by the enslaver, Thomas Jefferson. His doctrines of natural rights have come down to us as lessons in agency. It is our task to transform our self-conception into a sonorous chorus of diverse voices that would sustain our democracy.

By fighting for political and economic equality, we can, after all, make Lincoln’s “last best hope of earth” a reality. Contrary to Henry Billings Brown and John Roberts we can fight using the truth where “right makes might,” and using the future majorities in Congress reflective of the population in the states. We need a Supreme Court that will follow those majorities in the country not the individual wills of reactionary justices like Brown who refused to accept the “plain words” of the 14th Amendment. The current majority is a similar reactionary force which mimics the tortured logic of the Brown court. Roberts and his cabal corruptly voted for Dobbs and for the demise of affirmative action. We must prevent these racists from taking away our rights. The majority of Americans must stand up and take back our democracy.

Footnotes

(1) For a reference for the standing question see:

https://www.yalejreg.com/nc/associational-standing-in-the-affirmative-action-cases/

For a reference to the discrimination question see the Report of David Card PhD

December 15, 2017.

For the arguments by Justice Sotomayor see her dissenting opinion in the Students Case passim.

Also see the book review by Lawrence Tribe in the NY Review of Books, on books about reforming the Court published 8-17-23 p.50. When discussing Dobbs he quotes one of the authors, Joan Biskupic, the court's decisions have become “markedly non-judicious” and he comments on p.51 that the arguments even lack a“thoughtful rebuttal.”

(2) Plessy v. Ferguson substantially taken from Documents of American Constitutional and Legal History The Age of Industrialization to the Present volume two Melvin I. Urofsky ed. Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. The extra quotes are from the original full decision here:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/163/537

Here is the seven page pdf the students will read to take sentences from the opinions:

(3) See my lesson The Tarzan Theory of Reading here:

https://open.substack.com/pub/historyideasandlessons/p/the-tarzan-theory-of-reading?r=710fi&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

(4) In my classes an ID was 125 words with 2 examples in AP, 75 with one example in a gifted class and 55 in a Regents class with one example. The requirements were a definition of the topic, a year, examples of the subject and a sentence at the end that must say Plessy v. Ferguson was important because....” This was the only rigid format I required. On tests in the gifted and Regents classes the students would write 10 or 15 point IDs.

(5) The Slaughterhouse Cases can be found here:

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep083/usrep083036/usrep083036.pdf

Here are the excerpts from the Slaughterhouse Cases used above:

(6) It is incumbent on me to point out that at the beginning of his argument Justice Miller, who wrote the Opinion of the Court in the Slaughterhouse Cases called the Black people “the slave race.” See p. 70 for the reference in note 5 above.

This appalling phrase stands on a par with the phrases of the Dred Scott Case.

(7) Find the Frederick Douglass quote here:

https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/1860-frederick-douglass-constitution-united-states-it-pro-slavery-or-anti-slavery/

Find the Curtis dissent here:

http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1826-1850/dred-scott-case/justice-curtis-dissenting.php

Find the Murphy dissent here:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/323/214#writing-USSC_CR_0323_0214_ZD

See paragraph 65

48 Market Street PMB 72296, San Francisco, CA 94104

Unsubscribe